In 2001, we had email, chat, web browsing, instant messages and news bundled into one service. It was better known as America Online. With 35 million subscribers in October 2001, the online access empire faced the beginning of its end with customers rapidly churning out. While there are many reasons for the company’s decline, such as broadband usage, increase of competitors and increasing customer service issues — I believe one of the factors was users’ desire to unbundle their online experience.

I remember the days of signing into AOL and being greeted with a slightly digitized male voice, “Welcome, you’ve got mail!” Maybe you remember this as well. If you don’t know what I’m talking about, I must be getting old. For a little over 30 million people, AOL delivered all the value they needed to function on the web. They offered users features within a single, all-in-one experience. While a lot of people enjoy denigrating AOL, I have always viewed them as pioneers that introduced millions of people to the Internet.

The decline.

In AOL’s decline leading up to 2008, the company was presented with two choices to respond to customer churn. They could decentralize their services, effectively adapting to the needs of their maturing users. Or, they could clench their fists tighter preventing customers from falling through their fingers like sand. As history and personal experience would teach us, AOL chose the latter.

In one of the company’s most embarrassing incident, their maliciousness was documented when a customer tried to cancel service and recorded his conversation with a one of AOL’s retention employees. While the agent was aggressive, this behavior was acceptable and rewarded by the company. He was later terminated due to the bad publicity. You could say that Ferrari drove the second-to-last nail into AOL’s access business.

The last and final nail was when Texas and 48 other states banded together to coerce the company to amend their cancellation policies, implement a self-service cancellation method and refund affected customers.

AOL tried their best to drive usage of their software. In some respects, their moves added “convenience,” but to most others, it was a nuisance. The software was designed to startup automatically, stay resident in memory (to give the illusion it was faster), hook into the computer’s network adapters and was frustrating to uninstall. The proverbial line drawn between convenient software and aggressive adware, AOL routinely crossed it.

Besides going on a tangent about its aggressive retention policies, I want to share how unbundling could have helped AOL remain relevant today and even still have a thriving access business.

Why did users leave AOL?

A natural conclusion about why people left AOL was the cost of the service. I disagree. It was the value—or a lack of it when people realized they could receive their connectivity to the Internet from others. It wasn’t that connectivity necessarily was cheaper, it was better. At the time in the early 2000s, I remember 1.5Mb DSL cost us $50 per month. But it yielded a 20X improvement of access speed. Even pre-broadband, independent ISPs offered dial-up access for $10 per month with no software to install.

As an online consumer, we discovered that we could either purchase broadband or a cheaper dial-up alternative. AOL’s cash cow was not the money people paid to use their service, but it was the advertisements delivered to users. The company’s ARPU was a healthy multiple of the MRR paid by subscribers due to the advertising arm of the company. Of course, no business would refuse any amount of cash that people are willing to pay. In its earlier years, the company’s CAC was approximately $30, which resulted in a CLV of $350.

We realized we could take our online relationships with us with AOL Instant Messenger, which kept then-departed users within reach of AOL advertising and programming. It was the way to communicate with people outside of email. Plus it was fun and we all remember coming up with a clever Away Message; in retrospect, much like an early precursor to Twitter-like status updates. Despite attempts to keep their message service secure from competitors, the OSCAR protocol eventually was reverse-engineered and multiple ad-free IM clients emerged. Ultimately, AIM eventually fell from its leading place as the messenger of choice due to the ads it continued to deliver and lack of features that users wanted.

Outside of AIM, users discovered other means to achieve their goals. Yahoo and Microsoft (MSN) rivaled AOL’s features and was available free. Similarly, every ISP that users defected to offered e-mail as one of their primary features. Replacing the need to remember AOL Keywords (shortcuts to content), entered two powerful and user-friendly services to discover websites. AltaVista and Google. Anything users wanted was available without paying beyond their connectivity fees. They were in the driver’s seat and could get access to any content without barriers. Also, relying on easy software (Internet Explorer or Netscape Navigator) without the use of proxies, the online experience was simply better.

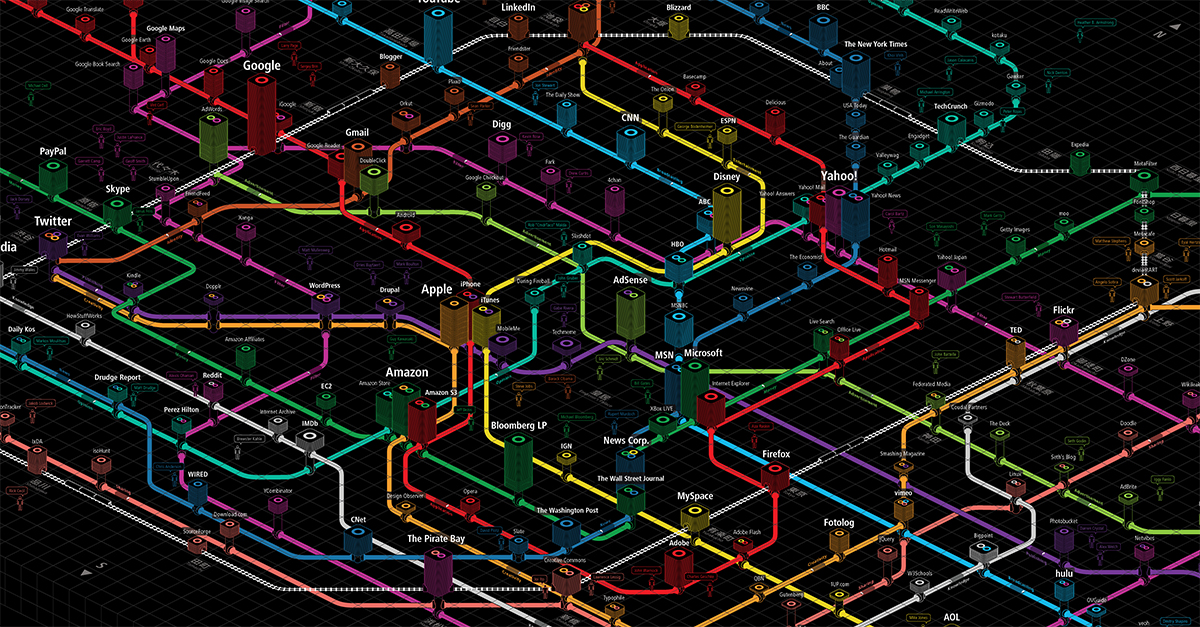

Effectively, the online experience became unbundled. Value was achieved and spread through multiple services. Instead of one carrier deriving all the value, startups thrived as they earned their fair-share of user activity and monetization.

The missed opportunity.

Instead of AOL securing deals with telephone companies to drive broadband sales, they fought to retain their dial-up access unit. And failed, miserably. AOL could have secured partnerships where there was a revenue-sharing, premium content promos and even upsells for bundling with other cable/phone services. AOL missed their opportunity to become the HBO of the web. And that would have been a very profitable opportunity. Internet usage exploded all while this happened.

This wasn’t AOL’s fault. It was their parent company’s fault, Time Warner. Time Warner always viewed AOL as a conduit to drive their print media sales. When the broadband exodus arrived, they predictably only recommended Time Warner Cable or other-affiliated carriers for users. And instead of offering attractive prices, they only shaved a few percent off the subscription. Remember, AOL’s cash cow was not the subscription fees, but the advertising revenues driven from active users. This was a death-knell when users didn’t feel it was necessary to pay for two ISPs.

It’s debatable if you think AOL authored decent software. It’s my belief the company did an excellent job at making software easy to use. It worked. It scaled. After AOL 9.0, it was evident that the innovation train pulled into the station and didn’t chug anymore. The company made a number of notable acquisitions and could have offered a variety of software apps that kept users engaged. After mixed success with bundling AOL and McAfee together, they nixed co-branded software together. Ultimately, the company folded their software development operations and ceased their idea-incubation functions.

AOL could have profitably switched to a free service years before 2006. Little did we know, Facebook nailed this strategy less than four years after AOL pivoted to become a content and advertising empire.

Facebook is what AOL could have been.

Today, Facebook’s more than one billion users dwarfs AOL’s climax of 35MM users. The company’s model is similar – keep users coming back to their online experience. Track data on users and sell advertisements on the backs of users to generate revenue. They offer messaging, content sharing, photo albums, groups and basic website creation (Pages). But instead of requiring users to use a desktop client, they drove users to the web and stayed ahead of the curve on mobile device usage. Ultimately, they made every reasonable effort to maintain a pleasant user experience.

Users are willing to sacrifice their privacy when they receive value. Users will not cancel their accounts if they receive meaningful value. Even if their online habits can be targeted, if they can like and comment on a friend’s baby photo or share a funny video – they will continue it. This activity gratifies some of our very own human needs.

Facebook’s financial model is that each user yields a practically non-existent CAC and unlimited LTV (due to no churn). They don’t drive as much revenue per user as AOL did, but they attracted more than 300X as many users. In short, Facebook continued where AOL left off by making the user experience clean, organized, sticky and easy to use. Oh, and developer-friendly. They now have more data on people’s interests than people can fathom and their ads platform is their thriving cash cow.

Back to Unbundling.

The Facebook Company is on a mission to unbundle their apps to drive engagement. The earliest example of this mindset is instead of keeping Facebook online identities all their own, they allowed developers the ability to authenticate users with their Facebook credentials, increasing customer conversion and convenience for end users. Their Facebook identities became their online passport they used to access online service. (AOL had their ‘Screen Name Service’ and Microsoft had ‘Passport’, but they did not allow third-parties to use these single-sign-on offerings.)

Another instance of unbundling is when Facebook removed the Facebook Messenger from the core Facebook client. They have compelled users to install their always-on messenger service. When the company acquired Instagram for a cool billion dollars, they didn’t kill it; they embraced it. They offered the app preferential viewing on the Facebook feed and easy sign in for users. I predict that Facebook will open up their calendar feeds and will refresh their Groups experience to be removed from core within the next few years.

Thinking ahead.

When you unbundle your offering, you deliver value in different ways. Users no longer use your software, but they use your platform. Over the years, I’ve seen online user trends shift from craving “all-in-one” bundles to fragmented unbundled offerings. And instead of bouncing back, the unbundled offerings now offer easy, powerful and seamless integration with APIs.

It’s my opinion that companies should look at what they are good at and decide on what they can sacrifice. Does Toyota really need to create their own feature-limited in-car navigation screens? Or can they leave that to Google or Apple to create entertainment interfaces for users (e.g., tablets)? I think they could. And with Apple and Google’s recent moves to battle it out for in-car entertainment, this will be an interesting war to lock users into their respective platforms.

Think ahead of your user’s interests and desires to plan for their departure. Plan for diversifying your solution so it become a platform. This allows others to hook into your benefits, your data and your overall brand equity. It also allows you to hook into other incumbents or emerging trends within your industry. Failure to do so could mean your service becomes a distant memory like, “Welcome, you’ve got mail!”

This post is a part of my 60 days of blogging. Read more about #60DOB.

Photo credit: Information Architects, Inc., Web Trends Map 4; Kenneth Saborio.